If a vehicle was coming through this intersection would this pedestrian have right of way? Stephen Di Donato/Good Free Photos

If a vehicle was coming through this intersection would this pedestrian have right of way? Stephen Di Donato/Good Free Photos

You are walking east on a footpath and come to an unmarked intersection without traffic signals. A vehicle is driving north, across your path. Who has right of way in Australia?

Should you step into the road expecting the vehicle to slow down or stop if necessary? Is the driver legally obliged to do so?

And does the driver see you? How fast is the vehicle going? Can it stop?

Now imagine you are the driver. What will the person on foot do next?

So the answer to the question of “giving way” is complicated. It depends on the speed of the car, how fast the person is walking, how quickly the driver reacts to apply the brakes, the vehicle itself, road conditions and how far the car and walker are from each other. Ideally, both the driver and walker can assess these things in a fraction of a second, but human perception and real-time calculation skills are imperfect. At higher speeds, both pedestrians and drivers underestimate vehicle speed.

Soon we will have to seriously consider autonomous vehicles, which can assess distance and speed almost perfectly, but there is still that ambiguity.

Read more: Driverless vehicles and pedestrians don't mix. So how do we re-arrange our cities?

What does the law say?

Road rules legislate how drivers should behave. But it turns out most people do not know right-of-way rules.

In Australia, the National Transport Commission recommends model rules, which each state adopts and lightly modifies. For instance, New South Wales Road Rules 72, 73 and 353 cover pedestrians crossing a road.

Rule 353 says:

If a driver who is turning from a road at an intersection is required to give way to a pedestrian who is crossing the road that the driver is entering, the driver is only required to give way to the pedestrian if the pedestrian’s line of travel in crossing the road is essentially perpendicular to the edges of the road the driver is entering - the driver is not required to give way to a pedestrian who is crossing the road the driver is leaving.

Because of the legal principle of duty of care, drivers must still try to avoid colliding with pedestrians. They have a legal obligation to not be negligent. Thus, they must stop if they can for pedestrians who are already there, but not those on the side of the road wanting to cross.

However, this element of the NSW Road Transport Act is not made explicit in the NSW Road Rules. There is no statutory requirement in the road rules or elsewhere to give way to pedestrians other than as set out specifically in the road rules.

In contrast, NSW Road Rules 230 and 236 explicitly require pedestrians to avoid behaving dangerously around cars.

The published advice in NSW is:

Drivers must always give way to pedestrians if there is danger of colliding with them, however pedestrians should not rely on this and should take great care when crossing any road.

Does a slow-moving person’s higher risk of being hit mean they can’t cross the road? Shutterstock

Does a slow-moving person’s higher risk of being hit mean they can’t cross the road? Shutterstock

This statement is not supported by any road rule or other law.

Does the law as written mean a slow-moving person can never cross the street because of the risk of being hit? Only because duty-of-care logic indicates both the driver and pedestrian should yield to the other to avoid a collision is it possible for this person to cross without depending on the kindness of strangers. But the law gives the benefit of doubt to the driver of the multi-ton machine. Existing road rules permit drivers to voluntarily give way, or not.

Keep in mind the asymmetry of this situation. A person walking into the side of the car is silly. A car being driven into the side of a person, as happens 1,500 times a year in NSW, is life-threatening.

Read more: Pedestrian safety needs to catch up to technology and put people before cars

What do we recommend?

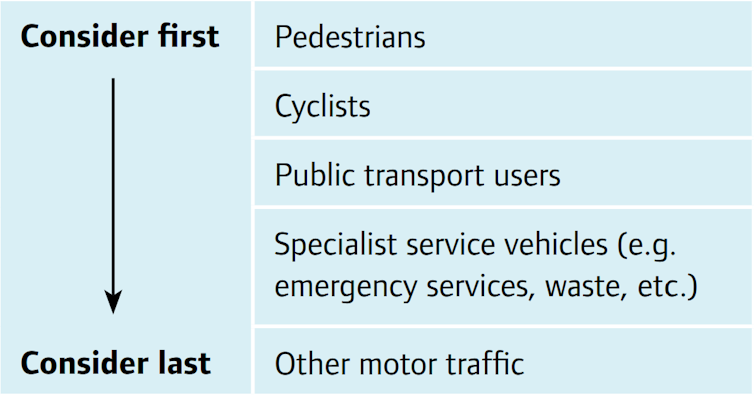

The UK Manual for Streets presents a street user hierarchy that puts pedestrians at the top. That is, their needs and safety should be considered first.

A recommended hierarchy of street users. Manual for Streets/UK Department for Transport

A recommended hierarchy of street users. Manual for Streets/UK Department for Transport

Walking has multiple benefits. More people on foot lowers infrastructure costs, improves health and reduces the number in cars, in turn reducing crashes, pollution and congestion. However, the road rules are not designed with this logic.

The putative aim of road rules is safety, but in practice the rules trade off between safety and convenience. The more rules are biased toward the convenience of drivers, the more drivers there will be.

Read more: How traffic signals favour cars and discourage walking

Yet public policy aims to promote walking. To do so, pedestrians should be given freer rein to walk: alert, but not afraid.

Like many things in this world, intersection interactions are negotiated, tacitly, by road users and their subtle and not-so-subtle cues. Pedestrians should have legal priority behind them in this negotiation.

The road rules need to be amended to require drivers to give way to pedestrians at all intersections. We favour a rule requiring drivers to look out for pedestrians and give way to them on any road or road-related area. In the case of collisions, the onus would be on drivers to show they could not in the circumstances give way to the pedestrian.

We believe all intersections without signals – whether marked, courtesy, or unmarked – be legally treated as marked pedestrian crossings. (It might help to mark them to remind drivers of this.) We should think of these intersections as spaces where vehicles cross an implicit continuous footpath, rather than as places where people cross a vehicular lane.

At this intersection in Surry Hills, NSW, vehicles cross a continuous footpath. Photo by David Levinson., Author provided

At this intersection in Surry Hills, NSW, vehicles cross a continuous footpath. Photo by David Levinson., Author provided

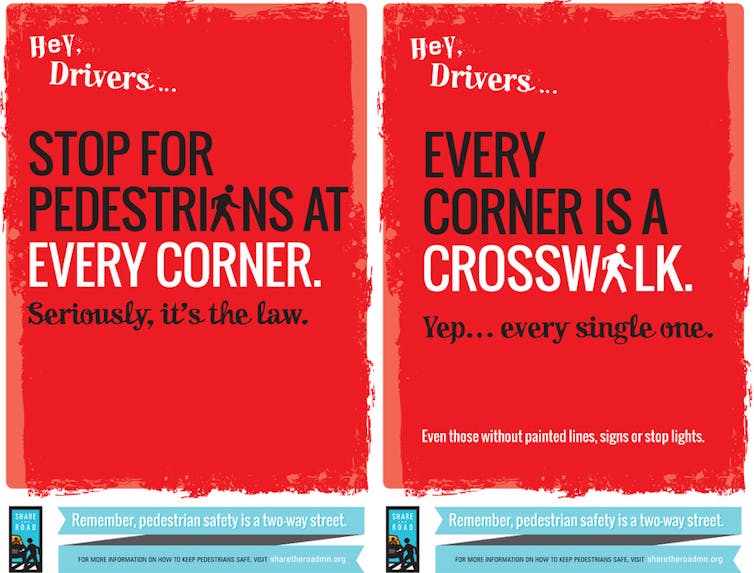

This change in perspective will require significant road user re-education. Users will have to be reminded every intersection is a crosswalk and that pedestrians both in the road and showing intent to cross should be yielded to, whether the vehicle is entering or exiting the road. We believe this change will increase safety and willingness to walk, because of the safety-in-numbers phenomenon, and improve quality of life.

In Minnesota, every corner is a crosswalk, marked or not, so stopping for pedestrians at intersections is mandatory, whatever direction the car is moving. Minnesota Department of Transportation., Author provided

In Minnesota, every corner is a crosswalk, marked or not, so stopping for pedestrians at intersections is mandatory, whatever direction the car is moving. Minnesota Department of Transportation., Author provided

Drivers should assume more responsibility for safety

People should continue to behave in a way that does not harm themselves or others. People on foot should not jump out in front of cars, expecting drivers to slam on their brakes, because drivers cannot always stop in time.

Read more: Nothing to fear? How humans (and other intelligent animals) might ruin the autonomous vehicle utopia

Similarly, drivers should be ready to slow or stop when a person crosses the street, at a crosswalk or not. But the law should be refactored to give priority to pedestrians at unmarked crossings. This will reduce ambiguity and make drivers more alert and ready to slow down.

In tomorrow’s world of driverless and passengerless vehicles, the convenience of drivers becomes even less essential. If someone is crossing the road, most of us probably believe a driverless vehicle should give way to ensure it doesn’t hit that person for two reasons: legally, to avoid being negligent; and morally, because hitting people is bad, as identified in many examples of the Trolley Problem.

Further, we should think more like the Netherlands, where vehicle-pedestrian collisions are presumed to be the driver’s fault, unless it can be clearly proven otherwise.

Read more: The everyday ethical challenges of self-driving cars

This article examined a few of 353 distinct road rules. Many others affect pedestrians and should also be re-examined.

This article was extensively edited by Janet Wahlquist of WalkSydney and extends some ideas developed as part of Betty Yang’s undergraduate thesis, but the text is the sole responsibility of the author.

David Levinson, Professor of Transport, University of Sydney

Image: Towards Data Science

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.