In response to the COVID-19 recession, federal, state and territory governments quickly provided support to the housing industry for two reasons.

First, to safeguard jobs and, second, because investment in the housing and construction industries has a high economic multiplier effect.

However, new research released today shows further housing stimulus measures will be essential to help drive an economic recovery into 2021 and beyond.

Our research found the various stimulus programs to date are too small to have a big impact on an economic recovery. It also found non-residential construction, followed by residential construction and then infrastructure spending, has the highest multiplier effect – the increases in activity and incomes that flow on through the economy.

The housing industry welcomed the A$680 million HomeBuilder grant and related state and territory measures announced in June to stimulate consumer demand. But, following such measures, our research suggests further investment focused on housing supply, in particular social housing, will be needed to sustain a recovery.

Read more: Why the focus of stimulus plans has to be construction that puts social housing first

The stimulus so far

The pandemic prompted numerous industry reports warning of huge job losses and recommending the best ways to support the housing industry. Most suggested multi-billion-dollar consumer stimulus measures. A number recommended massive investment in social housing.

Read more: Top economists back boosts to JobSeeker and social housing over tax cuts in pre-budget poll

Our research shows widespread industry support for the demand-side stimulus by governments. Cash grants have already increased new land and house sales significantly in most states and territories, which will feed through into building work. The exception is New South Wales where the HomeBuilder policy was not expected to have much of an impact in Sydney due to the A$750,000 price cap on eligibility.

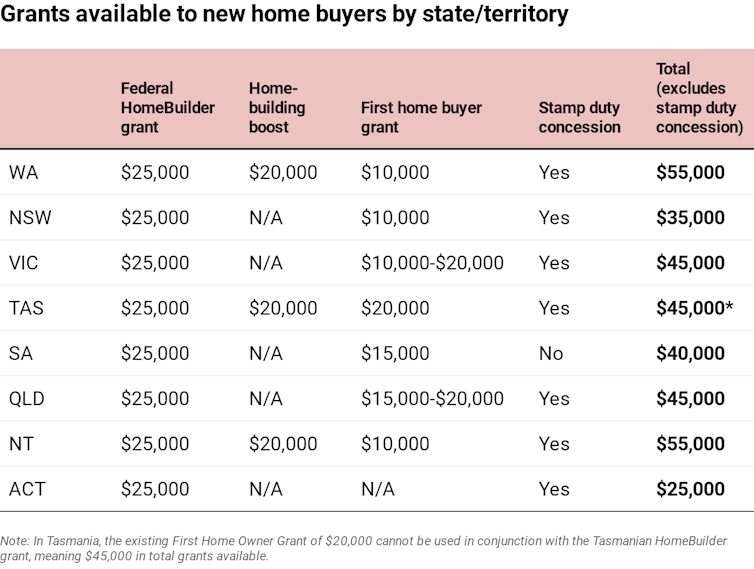

The table below shows the grants available to new home buyers in each state and territory. Stamp duty concessions are also available in all but one.

Author provided

Author provided

Given the size of this helping hand, it is hardly surprising many households are looking to take advantage of the schemes. The level of success in Western Australia has resulted in the state government announcing an extension to its building bonus scheme to meet demand and help sustain new building activity into 2022.

The building gap

Even before the pandemic, building activity had declined significantly. COVID-19 made things worse.

New dwelling commencements in 2019-20 are down significantly on just two years ago, ranging from a fall of 18% in South Australia to 29% in NSW and Queensland. The exception is Tasmania where commencements have risen by 15%. The total fall in the six states over this period is 53,000 commencements.

The federal government expects HomeBuilder to stimulate the building of 27,000 housing units, with the extended first home loan deposit scheme to add another 10,000 units. Much of this demand will be pulled forward from 2021-22, as tends to be the case with grants.

As a result, from mid-2021 yet more stimulus will be needed to sustain industry activity. This assumes population growth remains low.

Ultimately, if government is going to use the housing industry to support an economic recovery, the stimulus will have to be much bigger. This might just get the industry back to pre-COVID levels.

One way to plug some of the gap would be large investment in social housing. So far, though, only the states have committed to funding refurbishment and construction of social housing.

Read more: Social housing was one hell of a missed budget opportunity, but there's time

Compare the A$680 million HomeBuilder funding to the Australian government’s GFC response. The A$5.6 billion Social Housing Initiative delivered almost 20,000 social housing units. Another A$5.8 billion went into the First Home Owner Boost and Energy-Efficient Homes packages.

The Community Housing Industry Association (CHIA) has called for a A$7.7 billion federal stimulus package to expand Australia’s social housing supply by 30,000 homes. It has also detailed the economic benefits of such investment. Of course, there are long-term social benefits as well.

Read more: After COVID, we'll need a rethink to repair Australia's housing system and the economy

Further stimulus measures

Almost all interventions distort markets and most create unintended behavioural effects, such as people bringing forward existing plans. But we should remember that the housing industry, as a major employer, is an effective way to stimulate the economy.

Internationally, governments have been spending big on housing-related infrastructure, social housing and measures to improve the environmental sustainability of new and existing housing. Australia’s stimulus measures are small by comparison.

Housing activity is likely to slump when the current stimulus measures end. High unemployment and low population growth are not great ingredients for a building recovery. Industry will call for further support. While states have their own stimulus measures, they need support from federal government to stimulate the level of new build activity the economy needs.

Any further demand-side incentives should be tailored to the characteristics of individual markets and targeted where most needed – multi-residential development, for example. A one-size-fits-all approach will not work or be an effective use of taxpayer money. It is possible not all markets will require further intervention.

However, large-scale funding of social housing infrastructure is essential from a range of economic and social perspectives. For example, outcomes are more predictable because the number of extra units the investment delivers is more or less guaranteed. And this building activity is not reliant on private sector demand.

Immediate tax reform to encourage institutional investment in affordable housing and build-to-rent developments could help stimulate activity and deliver housing for those in need.

Read more: Build to rent could shake up real estate but won't take off without major tax changes

Governments need to pay attention to changing patterns of consumer demand and invest in areas with demand pressures. This is likely to be an issue in regional Australia where markets are often slow to respond to demand changes. Many households in the capital cities are showing interest in moving to regional areas as COVID-19 continues to shape preferences for different locations and housing designs.

The COVID-19 housing story is far from over.

Read more: How might COVID-19 change what Australians want from their homes?

Steven Rowley, Professor; School of Economics, Finance and Property, and Director, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Curtin Research Centre, Curtin University; Adam Crowe, PhD Candidate, School of Design and the Built Environment, Curtin University; Catherine Gilbert, Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Sydney; Chris Leishman, Professor of Housing Economics, and Jian Zuo, Professor, School of Architecture and Built Environment

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.