Brazil presents a very contradictory image to the outside world. The seductive face of Brazil is represented by its music, soap operas, football, innovative cities like Curitiba, and of course the delirious aphrodisia of Carnaval. However, Brazil is also the daily violence of its cities and the misery of its countryside. It has the world's highest national ratio of socioeconomic inequality and remains racked by violence, including the massacres of children and indigenous peoples, as well as by the record destruction of nature.

Opening of Emir Seder’s The Most Unjust Country in the World, an essay in the book, Evil Paradises, edited by Daniel Bertrand Monk and Mike Davis, (the recently deceased author of City of Quartz, the seminal analysis of LA).

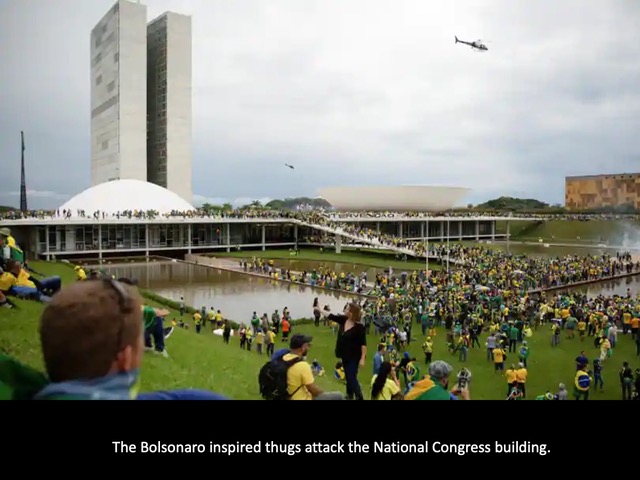

There is deep irony in the Bolsonaro supporters attacking the Brazilian Parliament buildings designed by Oscar Niemeyer.

These proto-fascists swarmed like yellow angry ants all over one of the key works by an architect well-known for his socialist beliefs, his atheism, and membership of the Communist party.

Irony and Niemeyer were well acquainted.

As a young architectural graduate, he was a talented draftsman, but he had to beg the established Lucio Costa to let him work for free. When Costa was appointed for the new HQ for the Ministry of Education and Health in Rio de Janeiro in 1936 he put together a team of rising architectural stars, and invited Le Corbusier as consultant. Again, Niemeyer had to beg to join the team.

But seeing Niemeyer’s drawing skills, Corb made him the key assistant, and when Corb left Rio, Niemeyer was so much in command of the scheme that he made significant changes, and improvements, such that by 1939 Niemeyer oversaw the design team. Some turnaround.

International recognition followed as he was seen as the progenitor of ‘Brazilian Modernism’. Niemeyer and Costa designed the Brazilian Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, and Mayor La Guardia gave Niemeyer the keys to the city. But fame really came in 1943 with the Saint Francis of Assisi church in Pampulha, a catenary structure so radical that the conservative church authorities refused to consecrate it for 16 years, no doubt pleasing the atheist Niemeyer’s greater belief in architecture than God.

Niemeyer returns to New York to work with Le Corbusier on the United Nations building, but the UN appoints the careerist Wallace Harrison, Director of Planning, to finish the design. Corb and Niemeyer are pushed out. Despite having keys to New York City, his membership of the Communist Party means time and again Niemeyer is refused a US visa to work, when he is invited to teach at Yale in 1946 and invited as Dean of Harvard GSD in 1953. Their loss.

Back home in Brazil he is ‘número um’. In 1956 the new President, Juscelino Kubitschek, invites Niemeyer to organise a competition for a new capital, Brasilia, located in the dry interior. Niemeyer choses Lucio Costa as the winner, and Costa becomes the chief planner and Niemeyer the chief architect. Let’s just say, in lieu of any irony, that “the child is father to the man” here, and both are exceptional.

Comparisons with Canberra are sometimes made: remote capitals built from scratch, but Brasilia wins the speed stakes hands down: the centre is built within ten years; and at epicenter is the National Congress of Brazil. The building is based on bicameral democracy; two houses: the Chamber of Deputies (513 representatives from 24 parties) is in the ‘saucer’ and the Senate (81 members from 16 parties) is in the ‘dome’.

Brasilia is a both a modernist delight and a blight: magnificent heavy forms as beautiful formalist pieces set on a geometric board of way-too-vast wide spaces (you can substitute Washington or Canberra in that sentence). In Brasilia the functions of parliament live in a pedestrian friendly area, providing a picturesque backdrop that created the strong visuals during the protests. The building seems perfectly designed for a pedestrianised assault (that ramp entry!).

The true genius of Niemeyer is his ability to make the whole and the detail: the grand and the human scale. Then, and most importantly, to carry them through to the interior spaces that are just a spectacular. A rare skill, paralleled in the works of Alvar Aalto in Finland and in Japan by Fumihimo Maki.

Which is why the desecration by Bolsonaro’s thugs was all the more distressing; the smashed glass and broken interiors make one weep. It’s been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, a year before the Canberra Parliament House opened.

Not long after Brasilia was completed, in 1964 the Brazilian government was overthrown by a Military dictatorship, and Niemeyer was forced into exile. He visited Cuba and Russia and then settled in Paris, where he designed the remarkable Communist Party HQ. Remarkable for its almost swank bourgeois qualities in what one would assume was the home for worker-led earnestness.

Niemeyer is 78 when it is safe to return home in 1985, and he recommences practice, designing two more buildings in Brasilia (a memorial and a church!) but it is the astonishing Niterói Contemporary Art Museum that is the one most architects know, the most audacious building ever undertaken by a ninety-year-old. Niemeyer dies at the age of 104 in 2012, and you can read more of his amazing life here.

Brazil is a deeply divided nation in every way, particularly in urban design, with inequality that far surpasses that in the UK, USA or Australia. The essay headlined above sets out an all too bleak picture for Brazil, one that Lula is unlikely to be able to fix any time soon. For all the beauty of the work of Niemeyer, Lucio Costa and Lina Lo Bardi, Brazil’s cities are as deeply scarred as the Amazon. And we just saw a physical manifestation of that erupting violence of inequality.

Tone Wheeler is an architect / the views expressed are his / contact at [email protected].