The National Construction Code (NCC) includes mandatory regulations relating to condensation management. The change was made in 2019, and the move has generally been welcomed by industry professionals with many calling the step overdue.

The latest NCC came into effect on 1 May 2019, and has been adopted by all states and territories in Australia. Any changes introduced by the new NCC will, therefore, have an influence on all building permits approved after this date.

Condensation management: What’s changed?

The most significant change introduced by the condensation management regulations is that buildings in the colder BCA Climate Zones 6, 7 and 8 (all of the ACT, Tasmania and alpine areas, and parts of Victoria, WA, SA and NSW) must now have vapour-permeable sarking on the outside of the primary insulation layer so that moisture can escape the building envelope.

Another change is a new requirement for ventilation of the roof space in the case of exhaust ventilation discharging into this area.

The Energy Efficiency Provisions of the NCC 2019 further introduces verification of building sealing by air leakage testing. Air leakage testing is not yet mandatory for houses, but this inclusion in the NCC signals increased awareness of the importance of airtightness in achieving low energy use homes. It is expected that a minimum standard may be introduced with the next NCC revision. Airtightness and ventilation play a key role in moisture management.

Read more here.

How does condensation form?

The lower the air temperature, the smaller is its maximum possibility of holding moisture. The dew point is the temperature to which air must be cooled to become saturated with water vapour. When further cooled, the airborne water vapour will condense to form liquid water. When air cools to its dew point through contact with a surface that is colder than the air, water will condense on the surface. In built structures, condensation becomes noticeable when beads of moisture appear on non-absorbent surfaces.

Condensation can occur on various surfaces in houses simply because of a low external temperature (such as during winter) or due to the activities of the residents, such as showering, cooking, or simply breathing! It is estimated that a family of four can generate up to 20 kilograms of water vapour per day inside a home.

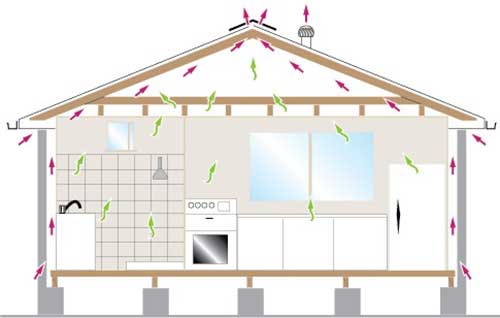

Under ideal circumstances, excess moisture will escape from the interior of the house through air vents, open windows and openings such as the chimney. Ventilation is the first line of defence in controlling condensation and should be considered for the spaces in walls, under floors and particularly under roofs.

Unfortunately, natural ventilation is reduced inside many contemporary homes and moisture is retained inside the structure, especially when windows remain closed during winter, for security reasons or for noise control.

Risks associated with condensation in homes

In 2015, a scoping study into condensation in residential buildings was conducted by the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) and the results were alarming, indicating that up to 40% of new buildings in Australia showed signs of condensation and mould.

Condensation can lead to various costly and dangerous risks, including:

- Health risks: Unseen mould growth behind wall linings and external cladding can be a health risk to the occupants, particularly the young or elderly, or those with asthma and/or allergies.

- Visual deterioration: Bending or staining of plasterboard linings. Moisture trapped behind the linings can cause unsightly water stains and swelling. It can also lead to the blistering of paint and a musty smell inside the house.

- Structural decay: Moisture trapped within the structure can have devastating results due to corrosion of metal structures, timber rot, loosening of nails as timber swells, and cladding rot or swelling.

Condensation and plasterboard

Plasterboard is susceptible to water damage and it is important to reduce condensation on all plasterboard surfaces. This is of particular importance in external plasterboard ceilings, such as in alfresco areas, carports, balconies and breezeways with plasterboard installed horizontally, or sloping away from the main dwelling.

We recommend that no plasterboard is installed until the building is waterproof, particularly in coastal areas subject to sea spray. In external areas, plasterboard must only be installed after the walls, windows, doors and roof covering have been completely installed and sealed.

Condensation on the face or the back of plasterboard can result in joint distortion, sagging, mould growth and fastener popping. To minimise the effects of condensation, we recommend the following:

- Choose a water-resistant plasterboard such as Watershield or TruRock for external ceilings.

- Use moisture barriers, sarking and insulation according to NCC regulations.

- Install eave vents, gable vents and roof ventilators in the roof cavity to improve ventilation.

- Remove humidity from bathrooms and kitchens with properly installed extractor fans.

- Use a quality paint system to provide protection against paint peeling and condensation soaking into plasterboard and compounds.

- Ensure the building design controls condensation on the steel components so that they are not constantly wet.

- In hot and humid climates where the building is air-conditioned to below the dew point of the outside air, the wall and ceiling framing members and internal linings should be fully protected by moisture barriers to separate them from the humid external air. The moisture barriers should be thermally insulated to maintain them at a temperature above the dew point.

- Thermal insulation is recommended directly above the plasterboard. This will minimise the temperature difference between the plasterboard and outside air, limiting ceiling sag and mould formation by reducing condensation on the plasterboard.