Australia, we need to talk about who governs our city-states

There are state governments, which are meant to represent the whole of the state but of course are most concerned with the single biggest city (as that’s where most voters live), often neglecting the rest of the state. And there are local governments, none of which has responsibility for more than a small part of the capital city.

In 1971, a Time magazine article, titled “Should New York City Be the 51st State?”, observed:

States have not only short-changed and hamstrung their cities but are themselves the least creative and effective of the three levels of government.

Of course, the United States still doesn’t have a 51st state, but the issue of city governance remains alive and relevant to Australia. Our metropolitan cities have no metropolitan government.

There are state governments, which are meant to represent the whole of the state but of course are most concerned with the single biggest city (as that’s where most voters live), often neglecting the rest of the state. And there are local governments, none of which has responsibility for more than a small part of the capital city.

Perhaps it’s time to consider statehood for our largest and fastest-growing cities.

Read more: Metropolitan governance is the missing link in Australia's reform agenda

Statehood has long been granted to global cities such as Berlin and Vienna (in the German and Austrian federations, respectively).

What might not be so obvious in Australia is that all our capital cities are effectively on the way to being city-states. This has had huge consequences for social well-being, economic development and global competitiveness.

What’s the problem?

Global cities – cities with a significant role in the global economy – like Sydney and Melbourne are gaining more power. It’s in line with a global trend of social, economic, technological and political convergence on cities.

This trend is especially obvious in Australia – about 90% of us live in urban areas. The capital cities alone account for 67% of the population and roughly 70% of GDP. Each state and territory has a lonesome metropolitan centre, surrounded by much smaller “satellites”.

Sizeable political gaps have emerged between urban and rural areas. At last year’s federal election, 60% of seats were in our capitals.

The growth and changing role of metropolitan cities means we should rethink their governance structures to meet their need of a strategic vision built on agglomeration. It’s about maximising the benefits of having many producers and people located near one another.

Read more: The growing skills gap between jobs in Australian cities and the regions

Western Australia, for example, has one substantial city, Perth. Its other much smaller centres function mainly as satellites to the capital.

Perth has been ranked as one of the top ten global cities of the future. Today, however, Perth is a “Beta +” city in the most recent Globalisation and Work Cities Research Network (GaWC) rankings. This means it is a city that links only moderate economic regions to the world economy.

In comparison, California has Los Angeles (Alpha), San Diego (Gamma), San Jose (Gamma) and San Francisco (Alpha -).

Western Australia is therefore, relatively, a city-state. It has only one global city.

Of course, saying Western Australia is a city-state is rather absurd, right? By definition, a city-state is a political organisation at a microscale, like Singapore, Berlin and Vienna. Western Australia has a land area about 3,500 times that of Singapore and roughly 2,800 times the area of Berlin.

But it’s equally absurd that vast expanses of the state have to be connected to the world economy through a lonesome Beta city. The absurdity is in the dilution of agglomeration effects, which come only from higher population density. Singapore has about 8,000 people per square kilometre, Berlin almost 4,000. And Western Australia? One.

A natural evolution

But hold on! Doesn’t Perth have its own government?

Well, no. Perth, like the other capitals, is made up of local government areas (LGAs) controlled directly by the state legislature. Perth has 30 LGAs. Sydney has 35, Melbourne 31 and Adelaide 17. Hobart and Brisbane have six LGAs each and even the smallest capital, Darwin, has three. The exception is Canberra, governed directly through the ACT Legislative Assembly.

We need to look at adding a fourth tier of government, metropolitan government, that can help harness the agglomeration effects in global cities. This proposition was advanced by a 2018 CSIRO book, Australian’s Metropolitan Imperative

Read more: Our cities need city-scale government – here's what it should look like

But what would it do for people outside the capitals? How would the rest of Western Australia benefit from metropolitan government?

Lest the reader thinks I am picking on WA, I’ll elaborate my reasoning using the state where I live: Victoria. It’s not efficient for a state bigger than England (as is the case for every state and territory, except Tasmania and the ACT) to be servicing one metropolitan city.

Regional centres in Victoria, like Geelong, Bendigo and Ballarat, service Melbourne to their disadvantage. Why to their disadvantage? Because a global city like Melbourne absorbs capital – human, physical and financial capital – from these cities. These cities will remain satellites of the global city.

Read more: Regional cities beware – fast rail might lead to disadvantaged dormitories, not booming economies

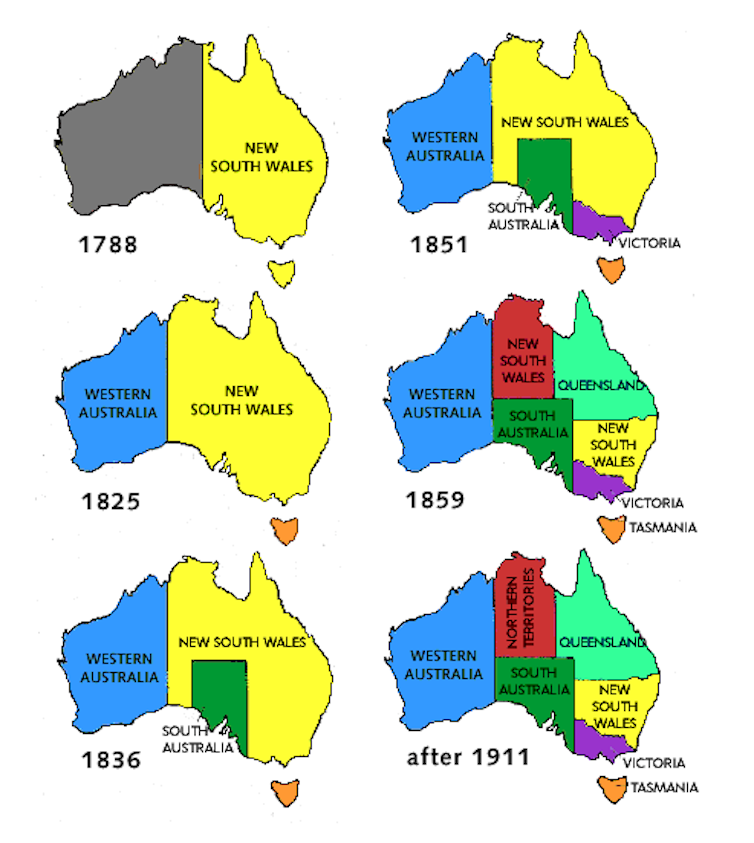

Think of the territorial evolution of Australia. Had Victoria not split from New South Wales in 1851, how likely is it that Melbourne would be a global city today?

To help the rest of Australia grow, the territorial evolution that started in the 19th century, and was interrupted in the 20th century, has to continue in the 21st century.

Note that this is an evolutionary argument. Over time, we expect more Australian cities to reach the level of population density and economic growth that would require statehood.

Read more: A patchwork of City Deals or a national settlement strategy: what’s best for our growing cities?

In 2013, demographer Bernard Salt predicted Townsville would become a metropolitan city by 2026, with more people living in north Queensland than in the state of Tasmania. North Queensland statehood would only help this evolution, just as it helped Brisbane in the 1800s.

In 1949, David Henry Drummond, who served in the House of Representatives and in the NSW Legislative Assembly, noted:

It is significant that since the Imperial Parliament handed over the control of Australia to the Commonwealth, no new State has been created, notwithstanding that Sir Henry Parkes, the founder of the Federation, said – ‘that as a matter of reason and logical forecast, the division of the existing colonies into smaller areas to equalise the distribution of political power, will be the next great constitutional change’.

The imperative for the Commonwealth is to pursue this “great constitutional change”. At the very least, it’s time to have a healthy national conversation about how we can boost our capital cities’ global status through a new drive for statehood.![]()

Benjamen Franklen Gussen, Lecturer in Law, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles