Sydney: A Biography is Louis Nowra’s love letter to his adopted city

Louis Nowra’s inspired biography of Sydney starts with a surprise visit to the city. He grew up in a housing commission estate in Melbourne. In 1959, while on a trip with his father to Wollongong in a truck to pick up a load of coke (for fireplaces, not drinking), his father took a detour – to Sydney. Nowra was nine.

Paul Ashton, University of Technology Sydney

Louis Nowra’s inspired biography of Sydney starts with a surprise visit to the city. He grew up in a housing commission estate in Melbourne. In 1959, while on a trip with his father to Wollongong in a truck to pick up a load of coke (for fireplaces, not drinking), his father took a detour – to Sydney. Nowra was nine.

After being driven through congested inner-city streets, he found himself on the Sydney Harbour Bridge. His amazement rendered him speechless. The massive grey steel structure and granite pylons provided a stunning contrast to the emerald-green harbour. Nowra’s passion for Sydney had been ignited. Twenty years later he moved to the now chic but then bleak inner-city suburb of Chippendale. Later, he took up residence on the border of the inner suburbs of Woolloomooloo and Kings Cross, where he lives today.

Review: Sydney: A Biography – Louis Nowra (NewSouth).

British economic historian R.H. Tawney famously said that to understand more fully places they were studying, historians needed “a stout pair of boots”. Professor Manning Clark echoed this in his 1976 ABC Boyer lecture, A Discovery of Australia. Nowra knew this instinctively, though he doesn’t claim to be a historian. Over the course of his long career, he has made his name as a playwright, novelist and a writer of creative non-fiction.

Nowra began walking the maze of criss-crossing, twisting and turning streets, roads, laneways, alleys, steps and paths that made up the inner city. Sydney was a disorderly place. It was not like Melbourne, with its mid-19th century, grid-pattern layout. In 1883, in his book Town Life in Australia, Richard Twopenny noted that “there is a certain picturesqueness and old-fashionedness about Sydney, which brings back pleasant memories of Old England, after the monotonous perfection of Melbourne and Adelaide”.

But Europeans had not shaped the veins and arteries of Sydney, as Nowra tells us. They appropriated Aboriginal walking tracks and pathways. The great grass highway to the south became George Street. The track which was renamed the (now Old) South Head Road created the northern boundary of Centennial Park, the largest urban park in the southern hemisphere.

Officers, officials, free colonists and ex-convicts built willy nilly, ignoring every governor’s instructions about building standards and the width of thoroughfares. Sydney was an accidental city. It grew like topsy. This was to lend the city part of its charm.

Geography and chance also played a role in establishing a place that was originally going to be called Albion, a literary term for ancient Britain, until the colony’s first Governor, Arthur Phillip, decided that naming it after Thomas Townsend, the first Viscount Sydney – a powerful British politician – might help his career prospects. Botany Bay, which had been chosen as the site for a settlement, proved unsuitable. While sailing up one of the world’s most spectacular harbours to the north of Botany Bay, Phillip found a stream of fresh water, at a place the Indigenous people called Warrang.

Phillip and his officers set up camp on the eastern side of the stream, where the first Government House was built. Some of its foundations can be seen in the Museum of Sydney’s forecourt. This set in motion the evolution of Macquarie Street, home to some of Sydney’s finest colonial buildings: the Mint, the Rum Hospital (now part of NSW’s Parliament House), and convict architect Francis Greenway’s magnificent St James’ Church. The convicts and their jailers camped on the western side, which became known as the Rocks. Mercantile Sydney grew there.

Pollution and unpredictable climatic conditions eventually crippled the Tank Stream. But it delineated what was to become the spine of the city’s central business district. Depending on the weather, occasional tours of the now subterranean stream – a “smelly stormwater drain”, as Nowra describes it – are available. Tickets are obtained through a ballot.

A city of water and stone

Nowra’s book is in part thematic. Water is a key theme. The Gadigal, the traditional owners of the land, were water people. For them, the harbour was a source of life. For the colonists, water could be treacherous.

A chapter on the tragedy of the Dunbar highlights the fear of ocean voyages and shipwrecks in the 19th century and beyond. In 1857, 121 people drowned during a storm when the ship’s captain accidentally ran the vessel into the sandstone cliffs at the Gap at Watsons Bay. Only one person survived. The incident has survived in the popular imagination. In 1930, Woollahra Council put the ship’s anchor on permanent display near the site of the wreck. An annual memorial service is still held at St Stephens Anglican Church in Camperdown.

Water was a source of other threats. During the 19th century, nervous colonists built fortifications around and on the harbour to defend themselves from invaders. Russians were expected after hostilities broke out with Britain in 1876. Bare Island in Botany Bay was constructed in response to this event. Over a century later, the island featured in the movie Mission Impossible 2. Nowra often connects places to popular culture, photography, literature and art.

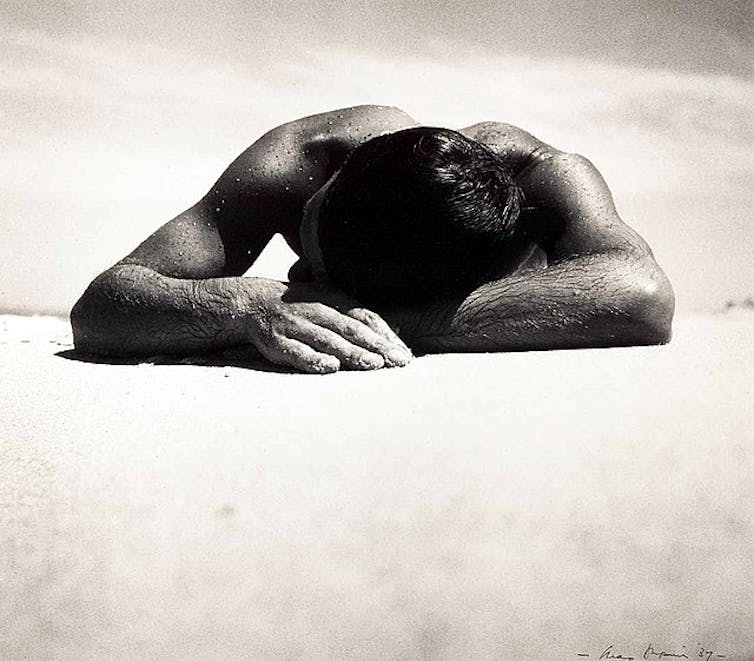

And then there’s Sydney’s famous beaches – Bondi, Manly, Coogee and Cronulla. Nowra spends a chapter on the long history of beach culture, from passive engagement with the water to the rise of surfboard riding, introduced to Sydneysiders in 1914 by the young Hawaiian surfer Duke Kahannamoku. He discusses Max Dupain’s photograph Sunbaker (1937) and Charles Meere’s painting Australian Beach Pattern (1940), both iconic images of the myth of the beach and body culture.

Sandstone is another important theme. Hawkesbury sandstone is found extensively across the Sydney basin. Sandstone caves and shelters provided housing for Aboriginal people for around 30,000 years. There is an abundance of rock art, most of which is hidden out of respect for these sacred items and for their protection.

The colonists hewed the stone to build the city. Much of it was taken out of quarries at Pyrmont and Ultimo. Many of Sydney’s grand Victorian and Edwardian public buildings are made of the yellowish, or at times greenish or grey stone. So too were bridges, churches, warehouses, stairs, street curbing, and the old sea walls built around the harbour to contain it.

The harbour is pushing back, slowly eroding the heavy blocks.

A playful history

Nowra uses a broad brush. His Sydney essentially takes in the inner-city suburbs of Woolloomooloo, the Rocks, Walsh Bay, Ultimo, Surry Hills, Chippendale and Redfern. It is bounded to the north by the harbour, as he acknowledges in the author note.

But Sydney is a city of many suburbs – 658 of them – and on a few occasions he travels out into some of the more distant ones. The chapter Mortdale, AKA Valley of the Dead recounts a recent summer excursion with Iranian photographer Ali Nasseri to this southern Sydney suburb. Quoting architect, urbanist and writer Elizabeth Farrelly, Nowra highlights a classic inner-city take on the outer suburbs. “The suburbs,” Farrelly wrote, “are about boredom, and obviously some people like being bored and plain and predictable. I’m happy for them.”

Farrelly seems to have changed her mind more recently, but this refrain has been circulating in the culture for over a century. Hugh Stretton strenuously repudiated it in his 1970 book Ideas for Australian Cities.

Nowra’s view is more playful. While he ultimately finds Mortdale unmemorable, it has its charms. The journey through Tempe and Wolli Creek opens his eyes to the massive contemporary redevelopment of these patchwork areas of old grey terraces, poor bungalows and worn-out paddocks. At Mortdale, he finds the culture is diverse, as are the inexpensive and generous food offerings. The main street gently throbs with all sorts of activities. And there is a sense of community – something that ebbs and flows in the inner city as money and property rights erase or ignore memories and traces of the past.

Nowra also has a chapter on A Day in Concord – a middle-class, 1920s suburb – though places like Concord and Mortdale are fascinating side trips in his book. He could have gone to Cabramatta, Harris Park or Campsie for other suburban experiences.

Sydney has numerous other faces, many of which Nowra unmasks. His book outlines a long history of corruption. For a decade from 1965, Sir Robert “Bob” Askin, the 32nd Premier of New South Wales, was a close friend to organised crime. Crown Casino was connected in recent years to money laundering. Police corruption was also rife until the 1990s, notably around Darlinghurst and Kings Cross – the subject of an earlier book by Nowra, and the first book in the trilogy of which Sydney: A Biography is also a part.

Then there is iconic Sydney – the Opera House, the Harbour Bridge, Luna Park and, for Nowra, the gleaming, green-grey tower of Crown Casino. Nowra acknowledges that a lot of people hate the city’s tallest building with as much passion as he hates the sculpture of Governor Macquarie in Hyde Park North, which he deems “the worst public sculpture in Sydney”. But this has no bearing on Nowra’s deep love of his adopted city. The epigraph from former Prime Minister Paul Keating captures his attitude: “If you don’t live in Sydney, you’re camping out.”![]()

Paul Ashton, Professor of Public History, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Popular Articles