Design notes for week 7/2024 from Tone on Tuesday

A column about design process, design policy and design and politics.A column about design process, design policy and design and politics.

This week

“Horses sweat, men perspire and women glow.” Traditional saying.

High humidity in the Eastern states, particularly Sydney, has raised much debate about its effect on thermal comfort, and how to avoid it. Here’s a quick rundown.

Sweaty days

Humidity is water vapour in the air, often expressed as a percentage (relative humidity) of total saturation (condensation, fog or rain results). If the temperature rises, and the quantity of moisture remains the same, the percentage falls. Conversely if the temperature falls, and the quantity of moisture remains the same, the percentage rises, and condensation happens at 100% (your house and car windows in winter).

A relative humidity of 50% is optimal; below 40% causes extremely dry air, leading to static electricity from friction (when you touch a metal cabinet in an AC building). Over 70% increases the feeling of heat, adding 5 degrees or more to the temperature sensed. There’s a sweet spot, or rather a sweet range, described by analysing the combination of air temperature and humidity in a Psychrometric Chart.

AC vs EC

There are two ways to combat the extra heat in summer: air conditioning, or evaporative coolers. The former has an (unreasonably) bad rap in sustainability, the latter’s no good in humidity.

Modern air conditioning was actually invented (by Willis Carrier) in order to dehumidify the air in tobacco factories in the Southern United States, not for cooling, for which it was quickly adapted. As AC lowers the temperature it increases the relative humidity, and some water vapour is condensed out, hence dripping water, or condensate, from AC systems. I’ve written too often about how necessary AC is to get cooling thermal comfort, but that it needs to be solar powered, to go further here.

Evaporative coolers use a lower-energy system that adds water to the air to lower its temperature, using energy in the air to evaporate the moisture and thus lower its temperature (latent heat of vapourisation). Widely used in the drier parts of Australia, it only exacerbates the thermal comfort in the coastal areas of Australia as it increases the relative humidity.

Good evaporative cooling

However evaporative cooling can work in high humidity, by evaporating moisture directly from the skin. The movement of warm air, even if humid, has extra capacity to remove moisture from the skin, thus lowering the perceived temperature with a sense of cooling to the skin.

Traditionally, the air movement was through cross ventilation, and our early houses were well designed for it. Some of the early white settlers in Australia had served time in India (as a British colony) and brought back the narrow single-storey bungalow (from Bangalore) and the veranda (from the Portuguese baranda in Goa).

When it was hot and the humidity was high, louvres on opposite sides could be opened and cross ventilation would result. These ideas are in the early Redicut timber houses in Brisbane and in the Burnett Houses in Darwin, with their deep shade, and louvres and single depth rooms. All hail the cross ventilation (X-vent), except…

X-vent is a contemporary disaster

As housing densities increase, with houses closer together, or townhouses or apartments, three things happen: the paths for potential breezes are reduced by the multiple buildings; the proximity of open windows brings more noise and a loss of quiet amenity for neighbours (think competing home theatres, or a divorce in the making next door); and in some higher density situations the air may be quite polluted.

Nevertheless, the myth of X-vent in higher densities is still touted nation-wide as a sustainable solution, it’s even enshrined as the best solution in NSW legislation (Apartment Design Guide part 4). This ‘guide’ has created myriad contorted shapes to achieve openable windows on opposite sides for 60% of apartments. Used as a ‘rule’, it is nonsense in two ways: why only 60%? and why bastardise the apartment plan, only reduce amenity for the occupants?

I’m a fan of another way

An alternative is very simple. Ceiling fans. A controlled method of air movement over the body in order to provide the thermal comfort. The introduction of ceiling fans to habitable spaces, living rooms and bedrooms, provides high levels of thermal comfort with very lower levels of energy use. They can augment cross ventilation, or provide cooling where X-vent is not possible.

Moreover, their greatest value is when there is the least amount of breeze, ironically when the highest humidity occurs. Even with every louvre open, there is no X-vent to save you then. Returning to India we see a similar solution with the Punkah; in Australia the wallah is replaced by electricity.

A simpler, more common-sense approach in rules such as the ADG, would make ceiling fans mandatory, even on balconies (as in SE Qld), which could bring higher thermal comfort at lower energy use.

Here's the biggest fan

There’s an irony here. One of the most popular makes of ceiling fans is the Big Ass Fan from the USA (as if the crass name didn’t give it away). What many don’t know is that they were developed by an Australian, Richard Aynsley, formerly a lecturer in the Architectural Science Department at the University of Sydney in the early 70s, where we attended lectures which we cruelly called “Dicks wind”.

Not such a big fan

After all that you’d think every design I do has ceiling fans (today’s column is written under one). Not so. In two recent projects, I was novated over to the builders, a vile practice which regular readers know I despise, (with the Building Commissioner on that). Both developers then directed the builders to remove ceiling fans from our designs, even though they were written into the approval. They went to great lengths to amend the Basix report, just to save a little coin. Oscar Wilde’s Lord Darlington had something to say on that.

Vale Bruce McKenzie

Last Tuesday some of Sydney’s best-known designers bade farewell to Bruce Mackenzie, whom many in the Dixson room at the NSW Library regarded as Australia's finest landscape architect. ‘Of world stature’, according to Professor James Weirick.

Mackenzie developed an Australian character for landscape, using indigenous flora for public parks, pioneering thinking that produced places like Balmain’s Peacock Point (now Illoura Reserve) and it is for that most difficult of ideas that he is fondly remembered. So many sites in Sydney were blessed to have such brilliant designer, all self-taught, as Mackenzie.

Detailed obituaries and reflections can found at ArchitectureAU and Landscape Architecture.

Everything Electric Australia

Last weekend saw the exhibition Everything Electric Australia at the Dome in Sydney Olympic Park. Displays of all things electric: vehicles, solar homes, chargers, batteries, and engineering. It featured over 10 different makes of electric vehicles. Several large stages had continuous explanations of the possibilities and pitfalls for electricity use in all walks of life.

How far we have come, at least in exhibitions. Five years ago it was a modest display of 20 DIY cars organised by the AEVA Australian Electric Vehicle Association. Now thousands of visitors pay up to $40 per day to visit and collect information. The radical transformation of Australia to electrify Australia seems underway.

But it’s not all green shoots. EV charging can be infuriating (see last week’s Design Notes). Moreover, many architects face the quandary of advocating for all-electric developments, only find that the electrical infrastructure is not there. Rather, gas is still very plentiful and cheaper to connect. If the extra electric demand means upwards of $300,000 for a substation, developers will always take the cheaper gas option, and the all-electric project is doomed.

Electric Australia is a long way off if the extra costs for the additional infrastructure are borne entirely by the individual owner. The market, left to its devices, says yes to gas and no to electricity.

Bookends

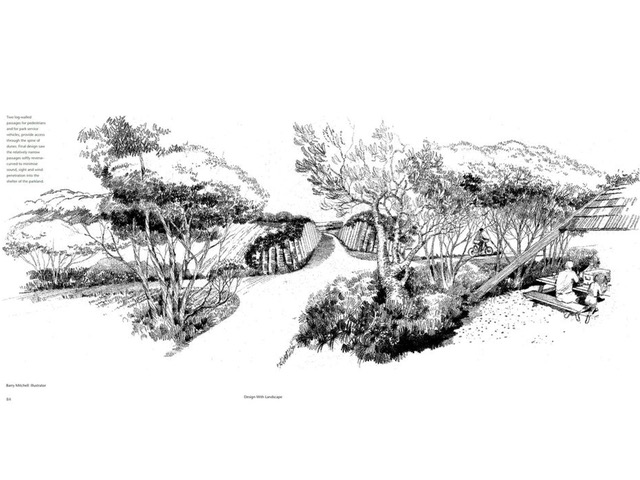

Can’t go past this fantastic tome from Bruce. Self-published, as was intended for the follow up on Urban Design which he was working on at the time of his death.

Signs Off

Tesla drivers can be relied on to really love their cars, if not their ‘cretin’ creator.

Next week

I’m off to Parramatta (Road that is).

Tone Wheeler is an architect /adjunct prof UNSW / president AAA.

The views expressed are his.

These Design Notes are Tone on Tuesday #195, week 7/2024.

Past Tone on Tuesday columns can be found here

Past A&D Another Thing columns can be found here

You can contact TW at toneontuesday@gmail.com

- Popular Articles