How our bushfire-proof house design could help people flee rather than risk fighting the flames

By 2030, climate change will make one in 25 Australian homes “uninsurable” if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, with riverine flooding posing the greatest insurance risk, a new Climate Council analysis finds.

By 2030, climate change will make one in 25 Australian homes “uninsurable” if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, with riverine flooding posing the greatest insurance risk, a new Climate Council analysis finds.

As a professor of architecture, I find this analysis grim, yet unsurprising. One reason is because Australian housing is largely unfit for the challenges of climate change.

In the past two years alone we’ve seen over 3,000 homes razed in the 2019-2020 megafires, and over 3,600 homes destroyed in New South Wales Northern Rivers region in the recent floods.

Building houses better at withstanding the impacts of climate change is one way we can protect ourselves in the face of future catastrophic conditions. I’m part of a research team that developed a novel, bushfire-resistant house design, which won an international award last month.

We hope its ability to withstand fires on its own will encourage owners – who would otherwise stay to defend their home – to flee when bushfires encroach. Let’s take a closer look at the risk of bushfires and why our housing design should one day become a new Australian norm.

Houses today are easy to burn

The Climate Council analysis reveals that across Australia’s 10 electorates most at risk of climate change impacts, one in seven houses will be uninsurable by 2030 under a high emissions scenario. This includes 25,801 properties (27%) in Victoria’s electorate of Nicholls, and 22,274 properties (20%) in Richmond, NSW.

Bushfires are among the worsening hazards causing homes to be uninsurable, and pose a particularly high risk to many thousands of homes across eastern Australia.

For example, the Climate Council found 55% of properties in the electorate of Macquarie, NSW, will be at risk of bushfires in 2030, if emissions do not fall. This jumps to 64% of properties by 2100.

The typical Australian house was not designed with bushfires in mind as most were built decades ago, before bushfire planning and construction regulations came into force.

This means they incorporate burnable materials, such as wood and plasterboard, and have features such as gutters which can trap embers.

What’s more, the gaps between building materials are often too large to keep embers out, which means spot fires can start on the inside of the house. And many houses are situated too close to fire-prone grasses and trees.

Indeed, at least 90% of houses currently in bushfire zones risk being destroyed in a bushfire.

How our new design can withstand fire

The prototypical bushfire resistant house we designed won first prize in the New Housing Division of the United States Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Solar Decathlon.

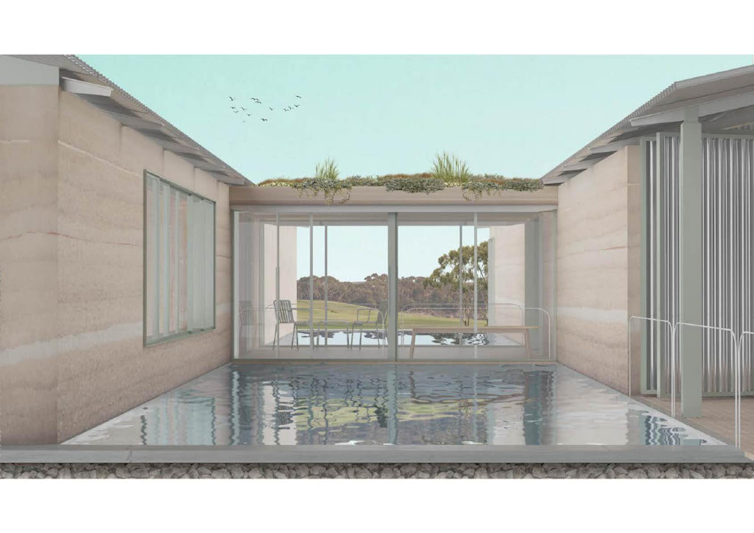

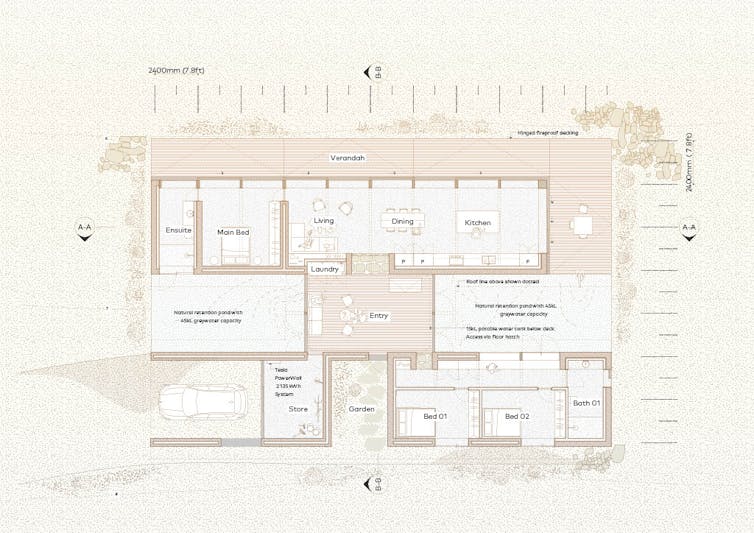

The house would be made from locally sourced, recycled steel frame. It would be mounted on reinforced concrete pilings to minimise its disturbance on the land, touching the ground only lightly. In this way, we help preserve the site’s biodiversity.

The primary building material is rammed earth – natural raw materials such as earth, chalk, lime, or gravel – which is not combustible.

The roof and some cladding are made of fire-resistant corrugated metal. Its glass facades have fire shutters made of fibre cement sheeting, a material that’s non-combustible and can be closed to seal the house.

Importantly, the gaps between these construction materials are 2 millimetres or less.

The sloped roofs tilt inwards to capture rainwater. And as the roofs are made of corrugated metal, which has channels in it, the house does not require gutters.

These channels guide rainwater into two open retention ponds either side of the entry, and into protected tanks beneath the house. This also helps protect the house in a bushfire, as it means the fire can’t penetrate from beneath.

When bushfires strike, the risk to life is highest when people stay and defend their homes. A design that can resist fire on its own encourages its owners to leave.

But it’s worth noting that it’s not a bunker for people to shelter in. No matter how well designed a house is, it always will be too dangerous to stay when a fire comes through, and particularly in the catastrophic and extreme fire conditions we’re increasingly experiencing.

It’s cost effective, too

The estimated cost of construction is between A$400,000 and $450,000. We deployed several strategies to keep costs down:

-

the house is designed to be energy and water independent, so will not need city utilities

-

it uses common construction techniques and is based on the construction industry standard for sheeting, so won’t require specialised builders and won’t waste any material

-

rammed earth is relatively inexpensive because it can be sourced in many locations, often for free. We also envision using recycled materials wherever possible.

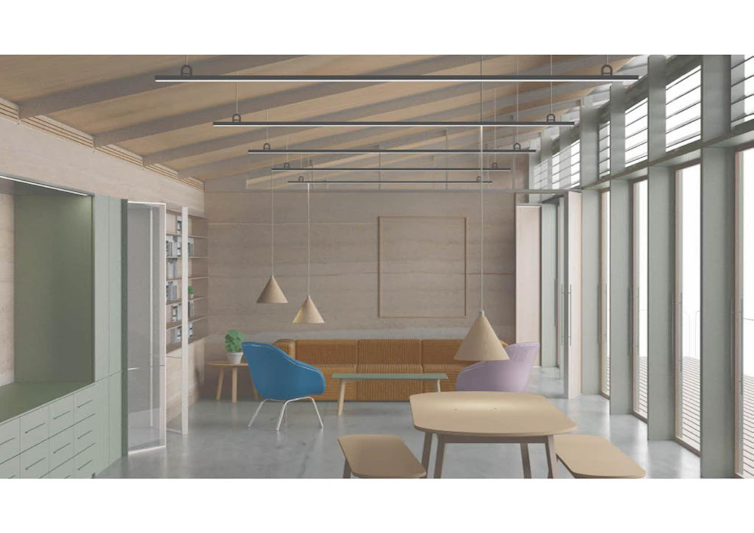

Aesthetically speaking, the design also presents an elegant domestic space, one that’s flexible enough it can easily be adapted to almost any site.

The next stage is to build and test a prototype of the house so we can evaluate its performance and make improvements. We’re currently speaking to some potential funders to make this happen.

As climate change brings worsening disasters, Australia must brace for thousands more houses becoming destroyed. Innovative architecture like ours offers a chance for treasured homes and possessions to survive future catastrophes.![]()

Deborah Ascher Barnstone, Professor, Head of School, School of Architecture, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.